Bo’ness, 22- 26 March 2017

“I am a woman and I’m full of viewpoints!” ‘Patricia’ /Marion Davies in The Patsy (1928)

After my first Hipp Fest experience last year I was delighted at the prospect of returning to Bo’ness for another sustained dose of Silent movie heaven! Regrettably I could only attend the final 3 days of the festival, but what I experienced was truly exceptional, joyously entertaining and totally immersive. Under the starry domed ceiling of the historic Hippodrome we were transported by the quality of musical accompaniment and the wonderful discoveries, creative innovation and artistry to be found when delving into the Silent era. Every performance is unique and as a member of the audience the thrilling immediacy of the whole live experience simply cannot be bettered. There are many ways into film, but the most potent trigger for love, appreciation and preservation of our global film heritage is the big screen experience. At Hipp Fest this is supported by highly experienced musicians responding directly to human stories, characters and themes projected before them in real time. This year audiences were blessed with the combined talents of some of the best Silent Film accompanists in the world including Frank Bockius and Günter Buchwald from Germany, Filmorchestra The Sprockets from the Netherlands, Stephen Horne, John Sweeney, Forrester Pyke, Mike Nolan, Neil Brand, Jane Gardner & Co and acclaimed musicians Raymond MacDonald, Christian Ferlaino and R.M. Hubbert.

Beyond the annual festival the universality of Silent Film which crosses all borders feels like a very timely focus politically, socially and culturally. Collaborative partnerships between Hipp Fest and its director Alison Strauss, the Goethe-Institut Glasgow, the Confucius Institute for Scotland, academic institutions and archives are vitally important in terms of sharing international film heritage and enabling cultural exchange. Bringing together never seen before films, restorations, live music and local audiences is one of the best ways of preserving film for future generations by making it proudly and publicly visible. In recent years the mainstream film industry has been justifiably criticised for its lack of equality and diversity. Ironically when the industry was still in its infancy there were more creative opportunities for women and studios were assembling the finest international casts and crews to challenge Hollywood dominance. In the Silent era women were much more powerful and visibly active behind and in front of the camera than they are in mainstream cinema today, working as directors, producers, writers and actors. Pioneers of the new medium creatively developed their techniques through experimentation, with the eternal baseline of visual storytelling in light and shadow. Although Silent Film is sometimes thought of as “niche”, “historical”, or “vintage” with the tone passing fashion, every Hipp Fest screening reveals that it is so much more in terms of being progressively modern, illuminating and visionary.

My first event was a talk The Last Silent Picture Show by Geoff Brown (film historian, critic, Chief Researcher on the AHRC-funded project ‘British Silent Cinema and the Transition to Sound, 1927-1933’ and a Research Fellow at the Cinema and Television History Research Centre, De Montfort University), examining the British Film Industry’s response to the advent of sound in 1929. The discussion caused me to reconsider the gains and losses from rapid technological advances in film production and publicity. Illustrated with clips from Hitchcock’s Blackmail, “the sentimental drama Kitty, the steamy White Cargo”, and “the tartan nightmare of The Lady of the Lake” this period of transition from Silent to Sound (1927-33) is fascinating in terms of stripping the medium back to its most essential, enduring elements. The development of sound may have been inevitable, but the overnight result was thousands of musicians and international actors out of work, with the insistence that stories must be told in the “the Mother tongue”. Arguably the most successful transitions from Silent to Sound were by artists like Hitchcock, grounded in the Silent Art of storytelling. Significantly Hitchcock’s approach to the new technology was not to have it dictate the vision, but to use it as another tool for the inner trajectory of the story and its characters. As Brown suggested, in Blackmail for example a conversation round the breakfast table emphasises the heroine’s state of mind focusing repeatedly on the word “knife”. Dialogue is a vehicle for suspense in that moment, on one level ratcheting up the tension with repetition; however on a deeper, psychological level it’s the character’s guilt that speaks to the audience rather than the word itself. Silent Film has a huge amount to teach contemporary artists about crafting moving images. Technology can’t do that on its own. The gift of now, regardless of future advances, is in retaining choices about how cinematic stories can be told. Brown’s talk on Silent, sound and hybrid productions raised many pertinent questions about current technology, artistic intent and what leads 21st century film production.

Friday night’s gala screening of King Vidor’s The Patsy (1928), starring Marion Davies, Orville Caldwell and Marie Dressler was the perfect film for getting into the 1920’s spirit and many members of the audience came along in Gatsby style fancy dress. Cloche, bowler and top hats, suits, tails and ties, feather boas, fans, sequinned and fringed Flapper dresses, gloves, black eye liner, beauty spots and pin curls helped set the scene with a friendly, welcoming buzz around the venue. The Patsy’s sparkling free spirited comedy was complimented beautifully by Filmorchestra The Sprockets: Daphne Balvers (soprano sax), Frido ter Beek (baritone, altsax), Marco Ludemann (mandolin, banjo, guitar), Jasper Somsen (double bass), Rombout Stoffers (percussion, accordion) and Maud Nelissen (piano), who also composed the score. Neilissen’s music brought a distinctive quality of worldly, feminine knowing to the central characters and their predicament, revealing musically the great unsaid in familial and romantic relationships. Brassy, exuberant Jazz was used to great effect in giving appropriate accent to the comedy on screen. This celebratory sound was charmingly contrasted with quieter, lovingly composed moments of intimacy on piano and mandolin.

The Patsy is a hugely appealing film due to the amazing comedic talent of Marion Davies, who film historian Kevin Brownlow aptly described as a woman whose “memory is clouded in myth”. History often assigns female artists the dubious honour of enduring fame by association with male partners. Davies is better known as William Randolph Hearst’s mistress and her fictitious alter ego-Susan Alexander in Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane than for her talent as an actress. Davies’ 35 year relationship with Hearst was very real, but it is only in contemporary audiences seeing her work that she has the opportunity to step out of the shadow of tabloid infamy and male genius to be what she truly was, a gifted artist in her own right. The audience response to the film resoundingly affirmed that quality, delighting in her attempts to “get a personality”, find her confident self and win the only man she has eyes for. Pat’s/ Davie’s impersonations of Mae Murray, Pola Negri and Lillian Gish, trying on the feminine stereotypes of vampish Femme Fatale or saintly goody two shoes are discarded in the end for something more authentic. Pat is constantly picked on by her proper dragon of a mother and spoiled sister, who is two timing Tony (the man Pat loves) and playboy Billy Caldwell. Her hen pecked father is seemingly the only person who sees her for the good natured, intelligent, witty and spirited young woman she is. Although she dreams of being as much admired as a stocking model, in the end all she has to be is her honest, down to earth self. This is a film of magnificent clowning and plenty of laughter, punctuated by genuine sweetness and sincerity, especially in the exchanges between father and daughter.

Silent Film provides surprising challenges to accepted norms of conditioning behaviour which are all too often frighteningly absent in contemporary mainstream content. Interestingly it is the mother figure who insists on Pat being relegated to a seen and not heard domestic role, while the masculine parental influence is infinitely more nurturing- rather like the relationship between Elizabeth Bennett and her Father in Austin’s Pride and Prejudice. The visual gesture and intertitle dialogue between father and daughter makes it clear that they regard each other as equals, sharing humour and emotional intelligence. Part of the joy of this film is the juxtaposition of manners with physical comedy and freedom of expression, revealing human hypocrisy and foibles we all know and recognise. The heroine is a feisty, independent alternative to the passive set decoration women are so often assigned on screen. Davies and her character Pat convincingly carry the film, offering a Silent reappraisal of gender roles and challenging the regressively persistent idea that brains and entertainment in Film are mutually exclusive. In The Patsy masculinity can be as tender as it is strong and femininity can be a three dimensional possibility rather than a polarised cliché of self-denial and sacrifice. The Patsy or scapegoat, someone cheated of their rightful place or taken advantage of, is actually women as represented in mainstream contemporary film. This charming, 1928 crowd pleaser delivers irrepressibly buoyant fun, but also the opportunity for reflection on what constitutes box office gold in our own century.

Twenty seven year old director Wu Yonggang’s 1934 debut feature The Goddess (Shen nu) presents a very different view of Femininity in the story of a mother’s love and self-sacrifice for her child. It is a film confronting the harsh realities of poverty, corruption, class oppression and moral decay through a Social Realist / party political lens. In the background of the opening intertitle cards we’re introduced to a Feminine ideal via the low relief Neo-Classical sculpture of a woman leaning down to the child at her feet. Tellingly her body is bent double, compressed into the rectangular frame, overwritten with the idea of the “double face” of a “Goddess struggling with life”. We are then quietly introduced through small everyday details to the central female protagonist, a prostitute by night and devoted mother by day. As the sun goes down the camera moves through her rented room, lingering on her two dresses hanging from a peg on the wall, her trade makeup, a doll and baby basket. As she tentatively looks in the mirror and dresses for the evening of work ahead the camera doesn’t judge her, it humanises and dignifies her as she prepares to walk the streets to earn a living beneath the harsh neon of 1930’s Shanghai. That empathic view was supported perfectly by John Sweeney’s accompaniment, well suited to the understated grace and presence of the unnamed central character who carries the entire film. She is presented as a noble figure battling reduced circumstances, trying to ensure that her son has a better future through education, a right denied to him by those in authority because of his mother’s profession.

The sympathetic portrayal of a woman condemned by her position in life and social hypocrisy is testament to Ruan Lingyu’s highly sensitive performance. The actress herself was the victim of crippling double standards and was literally hounded to death by the paparazzi. In Art and in life the public/media moral compass was tipped towards mass consumption of adulterous scandal and generation of headlines, rather than any interest in justice or humanity. The director Yonggang was inspired by D.W. Griffith’s tale of a wronged woman Way Down East (1920), which starred Lillian Gish as an innocent girl tricked into a sham marriage by a wealthy seducer and having to bear the shame of an illegitimate child. Yonggang’s central character is invested with subtlety and compassion, equalled by the marvellous cinematography of Hong Weilie and the understated skill of the accompaniment. John Sweeney consistently excels in capturing the emotional tonality of what we see on screen and was the perfect interpretative match for this film. His natural, gentle lyricism as a musician communicated the intimacy and trust between mother and son at the heart of the story. The rare opportunity to see this recently restored film was enabled by the partnership between Hipp Fest and the Confucius Institute for Scotland, supported by the China Film Archive. The special focus on Chinese Cinema through talks, screenings and performance provided an outstanding opportunity for local audiences to explore films and a cinematic tradition that is largely undiscovered in the UK and not easily accessed outside the festival.

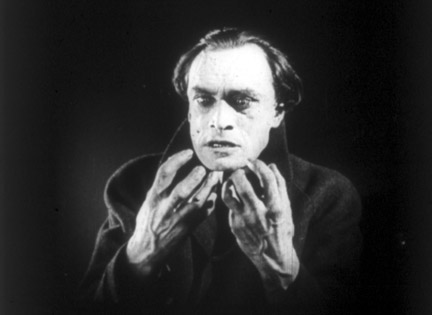

It was a great privilege to see two of Germany’s finest Silent Film accompanists Frank Bockius (percussion) & Günter Buchwald (piano & violin) performing Robert Weine’s fantastic 1924 psychological horror/ thriller The Hands of Orlac /Orlacs Hände. The feature was very appropriately paired with the 1908 short The Thieving Hand from the Eastman archive, featuring pioneering special effects and accompanied by the wonderful Forrester Pyke on piano. The ghoulish, seemingly supernatural subject matter of disembodied hands having a monstrous, amoral life of their own is actually a grounded concept given the time the film was made. The Hands of Orlac stars Alexandra Sorina, Fritz Strassny and Conrad Veidt (The Cabinet of Dr Caligari, The Man Who Laughs, The Thief of Bagdad, Casablanca) as Paul Orlac, a renowned concert pianist who loses his hands in a terrible accident. His devoted wife pleads for surgery so he will not lose his gift for music, but after new hands are grafted on, he learns that they belonged to an executed murderer and the nightmare begins! He starts to believe that the hands and will of the dead man possess him and that he too will become a murderer. It’s a film where belief, action, reason and the unconscious converge in unexpected ways. Having seen Frank Bockius perform for the first time at last year’s festival, I had hoped that we would again have the opportunity to experience his great talent and musical expertise. This year we were indeed fortunate to have two touring musicians from Germany with the continued support of the Goethe Institut Glasgow, expanding the possibilities for musical collaboration over several different screenings. What these performances communicated with such energy, intuition, precision and style was that Film History is resoundingly a living tradition! I hope that many more audiences in the UK will have the opportunity to experience Silent Film live as a result of this exciting and very fruitful partnership. Post Brexit continuing to nurture collaborative relationships and cultural exchange is now more vital than ever. The audience clearly enjoyed the psychological depth of the film, courtesy of the Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau Archive and its adept multi-textured accompaniment.

The opening melody, from the first movement of Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No1 in B flat minor, immediately established the voice of solo piano and the virtuosic stature of the central character. This grand, commanding theme supported by triumphant cymbals and drums evoked the scale of the concert hall in a highly charged, dramatic introduction. As the film progressed the sweepingly epic melody became increasingly deconstructed and fragmented as the darker aspects of the psyche started to take hold. When this melodic phrase is first introduced it is staid, classical, familiar and authoritative, but there is also a shadow present. It’s the shimmering uncertainty we hear in the gentle swish of cymbals and the otherworldly suggestion of phantom strummed piano wires that undermines the certainty of what we think we know. Sound is our most primal sense and the introduction of this quietly subtle undercurrent operated just like the sound that you hear in the dark, lurking just beyond your peripheral vision. As the fear of what the hands are capable of grows in the mind of the central character, the theme morphs into diabolical variation and full Body Horror takes over with the stabbing down stroke of the violin and drumming used in later scenes. The scope of percussion to propel, amplify and inform our internal reading of a scene was deftly handled throughout. An early scene where Paul’s wife reads his letter and awaits her beloved husband’s return is accompanied by a progressive, heartbeat-like rhythm communicating the emotional current between them. There is something undeniably human, shared by the audience in that essential, percussive beat we know within our own bodies. That deceptively simple sound triggers memory, engages empathy and imaginatively connects the viewer to the story and its characters, no matter how fantastical they may appear.

Although it would be easy to lay obvious “Horror” music on top of a film like this, the handling was much more compelling due to the sound approach of the fear that lies beneath. The accelerated crescendo of the train wreck with its bursts of light and sound was tempered by gentler suspense. The main melodic theme is modified into a dreadful question mark as Paul’s wife searches for him- is he still alive? In the aftermath of the accident semi abstract compositions of dark and light, machinery, debris and human figures in silhouette emerging through smoke, invoke the Horror of an ordinary day and homecoming turned into a scene of devastation. The cinematography by Hans Androschin and Günter Krampf is striking, moving between the language of realism, expressionism and surreality. The Art Direction by Stefan Wessely and Hans Rouc brings elements of expressionistic angularity and unsettling ambiguities of scale into domestic settings. These small details like the oversized geometry of a drawing room rug or elongated fairy tale-like chairs combine with the lighting to enhance our sense of entering into a heightened reality, somewhere between the conscious and unconscious.

In the nightmare of Paul’s foggy bedroom we see the vulnerable human figure dwarfed by a giant fist threatening to crush him. It is a powerful example of visceral horror through sound and image which has distinct political associations. Accompanying this scene Frank Bockius used his elbow, compressing the air inside the drum to create an inner depth of sound of frightening physicality. Within that sound was the feeling of compression in the chest cavity triggered by Paul’s fear of the murderer Vasseur’s hands which have become his own. Something from the real/physical world is fighting for his soul and murderous, unconscious instinct is masquerading as the supernatural. The sounds created by the hand played strings of the open upright piano expose the psychology of the character, with the controlled, circular motion of brush on drum intensifying our felt sense of unease. There were times when this technique took on a spatial dimension, entering into a mind cave of madness. It was then brilliantly taken to a whole other level in a scene where the ghostly dead criminal instructs Paul’s maid to “seduce his hands” and the circling movement of brushes intensifies as she crawls towards him on all fours. The piano is introduced as Paul places his hands on her head, one hand of the piano pitted against the other, with the plucked tension of violin and piano strings internalising the struggle between good and evil.

The technique of using a drumstick inside the piano and hand played drum were particularly effective in creating a sense of dread, being overwhelmed by the will of Vasseur’s “cursed, damned hands!” Strangely I hadn’t really considered the piano as a percussive instrument before but it is all hammers and wired tautness, something Buchwald exploited to the full as a manifestation of the film’s moral dilemmas. Paul symbolically hides the knife inside the piano and metaphorically inside his heart, but as the professor reminds him; head, heart and hands make a human being. “The hands don’t control the man”, the mind has ultimate control. In the context of the Weimar period this statement takes on prophetic relevance and profound irony. It is therefore not surprising that the doppelgänger emerges as a strong archetypal figure in the film. Whilst many cultures have tales of apparitions or the double of a living person associated with bad omens, the dark Romanticism of ETA Hoffman, Grimm’s fairy tales and Germanic folklore provide particularly fertile ground for exploration of the human psyche. The Hands of Orlac is a story about the power of belief which can bring damnation or redemption. When rationality usurps madness, Paul moves into the light declaring that his hands are clean. I thoroughly enjoyed the spellbinding, imaginative scope of this film, equalled by Bockius and Buchwald’s arresting musical accompaniment.

Whilst it is unrealistic to expect the same level of experience from a first time commissioned musician, as in all Art intention is everything. If an artist is fully engaged not just with their own performance but with the story on screen, then the audience will resoundingly feel it. This has nothing to do with musical style but the channelling of creative energy into something bigger than your own signature sound. Multi-award-winning, post-rock, Scottish composer and song-writer R.M. Hubbert (aka Hubby) is clearly a gifted guitarist and I enjoyed his acoustic sound, the problem was that often it had little to do with what was on screen. His newly commissioned score for the Soviet film By the Law /Po Zakonu (1926) relied too heavily on what I expect the artist already has in his back pocket when the imagery, themes and story demanded more. The film’s most striking sequences of human figures silhouetted against the luminous expanse of frozen landscape or the raw angularity of human faces in anguished close up, don’t chime with musical sequences of repetitive arpeggios and plodding rhythms. There’s real conflict in this film, in its moral dilemmas, its themes of man against nature and his/her own nature and the justice of law and religion, that is ripe for interpretation. Commissioned musicians have a unique opportunity to take an audience deeper into what they see on screen in new and innovative ways. The whole point is stepping out of your comfort zone and taking the audience on that journey of discovery with you-whether they’ve never seen the film before or have watched it multiple times. I felt as though I had discovered a film and a talented musician- just not together! Ultimately it was the visuals rather than the synthesis of sound and image that stayed with me. For this type of performance they have to equal each other, anything less than that is just a concert and in the context of a dedicated Silent Festival the difference is glaringly obvious.

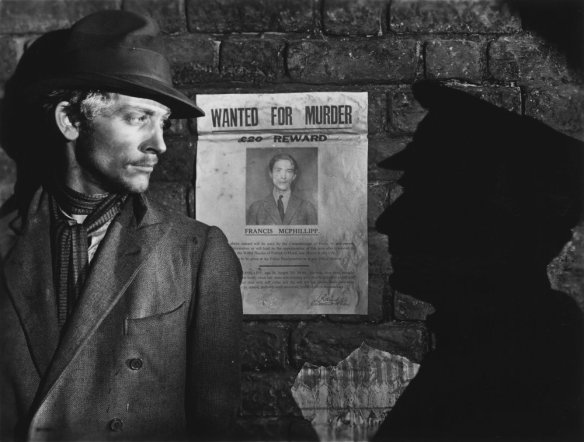

Newly restored by the BFI, The Informer (1929) was a great example of international collaboration both in its original production and in live performance at its Hipp Fest Scottish premiere. Filmed at Elstree Studios by British International Pictures the creative production team included German/ American director Arthur Robinson, Swedish Actor Lars Hanson, British actor Carl Harbord and Hungarian actress Lya de Putti, with design and cinematography by J.Elder Wills, Werner Brandes and Theodor Sparkuhl. The artistic roots and filmic techniques of German Expressionism inform the depiction of 1920’s Dublin and the internal conflicts of the characters perfectly. It’s a Noirish world of light and shadow gripped by social, cultural and religious upheaval. Personal and political motives are pitted against each other and the smallest actions have life changing consequences. The semi improvised collaboration between British and German musicians Stephen Horne (piano & accordion) and Günter Buchwald (violin) was an excellent match for this technically and artistically sophisticated drama. Set in the newly independent Ireland of 1922, the story centres on a group of revolutionary activists and a fateful love triangle. It’s a brilliant Proto-Noir, fuelled by jealousy and betrayal where each character progressively becomes an informer, pursued by their fateful shadow selves and caught in a descending spiral of cross and double cross. In this first adaptation of Liam O’Flaherty’s novel the inescapable consequences of being a flawed human being are cinematically heightened.

As a film of the transition to sound period the decision to restore The Informer as a pure Silent, retaining the texture and visual depth of the original purple tint undoubtedly brings audience closer to the story. Developed in Silent mode without the static restrictions of sound recording, the camera is free to move and follow the characters, not just in terms of external action but getting inside their heads. Conscious and unconscious motivations are revealed without the addition of clunky explanatory dialogue. What Silent visual language and great musical accompaniment does best is to immerse us in the entire human predicament in a way that frees us to construct our own inner dialogues. This is a whole lot more fun than being told a story via talking heads or pushing emotional buttons through a predictably conventional soundtrack! It is also what human beings are hard wired for- to construct meaning and narrative through imagination. The sonic expression of that principle is found in the work of the best Silent Film accompanists who don’t just provide illustration and sound effects but lead us deeper into the moving image, the story and ourselves.

Horne and Buchwald’s live accompaniment took its cues very skilfully from the film’s central protagonists and their fatalistic trajectory. This musical foreshadowing is felt almost unconsciously in the opening theme, with the lilting spirit of a Gaelic lament. The melody immediately conveys an atmosphere of inevitable loss, setting the tone for the unfolding drama. Musically it anchors the story to place, the identity of the characters and the soul of Irish (and Scottish) Folk music, whose double face is sublime sorrow in song, coupled with life affirming dance rhythms. That fiery vitality transforms the main theme in the opening scene at party HQ, where the strong down stroke of the violin aligns with the hand on table gesture in close up, insistent on life through liberty. Here the main melodic theme inspires action rather than reflection, mirroring the nature and intentions of the gathering. Whilst theme and variations can be a vehicle for obvious dramatic effect in less experienced hands, there was a deeper emotional investment in play in direct synthesis with the projected image. In the very next moment we are subtly introduced to the dynamics of the central love triangle, quietly revealing itself in the solo piano as Gypo offers Katie a cigarette. It’s an everyday gesture transformed into a moment of recognition by what we see and hear musically, leading us to our own conclusions about the nature of the relationships between the three friends. Sitting across the table from Katie who is arm in arm with his best friend, we share a moment of tender regard with Gypo that casts the die. That quiet repose is shattered by a gunfight utilising the rumbling depths and high wired tension of the piano’s full expressive range. In the chaos that ensues, the ricochet of bullets in broken minor stabs of shrieking violin and tinkling ivories of broken glass underscore the violence. When the fateful shot is fired and Francis descends the staircase the melody follows him like his shadow on the wall, echoing his darkening destiny. As he takes to the hills looking back in a high sweet fade of pianistic regret, the flute then takes over as the lone voice of the fugitive in hiding. The choice of instrumentation and timbre comes to the fore in terms of the inner emotional state of the protagonist and the audience’s ability to empathise with him in that moment.

The idea that this story will not end well is an integral part of the film’s suspense. When the ultimate destination is revealed to the audience we anticipate the arrival without knowing the road that’s going to take us there, which is what makes the ride so gripping! This progression towards the inevitable enters another interpretative level and emotional gear shift in a false scene of betrayal. The traditional melody She Moved Through the Fair is introduced on the accordion as Katie puts needle to the record to muffle the sounds of Francis’s escape. As the camera moves between action in different rooms of the apartment, variations in volume create a sense of physical space but also a haunted, distant quality in relation to the melody. The final notes that end the song lead the audience sonically and poetically into the ground/ grave. Even without ever having heard that song or having memory of the lyrics, its sound arc is ethereally fragile and resolves in loss. That sense of foreboding of death and lost love, moving in and out of time, is juxtaposed with what the character sees as proof of his sweetheart’s deceit, scratching away at his innards like the Buchwald’s violin bow. The filming of this sequence, where Gypo sees Katie helping Francis to escape in a mirror depth shot is immediately discordant, plunging us into his conclusion of guilt where in that moment there is none. The musical accompaniment informs what we see and increasingly feel, as jealousy overtakes him and the smoothly insidious sound of the violin takes over. He tests Katie and when she lies about not having seen Francis we see her shadow on the wall and from that frame onward we know that their three fates are tragically entwined. We feel it without being told or having it explained to us in words. Light, shadow and sound convey what is most essential in the scene. The artistry and understanding of Craft necessary to read and reinterpret film through sound is the accompanist’s greatest gift to the audience. The psychology of the music aligns with the inner world of the characters because of the musician’s honest, human and supremely skilled response to the film.

There are breath taking visual sequences in The Informer such as Gypo’s path to betrayal, the moment he sees the wanted/ reward poster and the violin staggers as he does towards what he about to do to his best friend. The camera/ audience follow him close behind, into streets teeming with life, his fixed purpose harnessed by a harsher variation of melody as his flawed self emerges. The sound moves through our consciousness as he moves through the world, on a certain path to destruction. When the deed is done and Gypo protests that he “didn’t do it for the money” the piano creeps softly into his conscience, perfectly in sync with the pace and emotional tone of his walk, carried in the body and his attendant shadow self. There are beautifully crafted visual elements of what might have been in the reflection of a smiling male mannequin in the shop window, contrasted with the actual exchange between Katie and Gypo underpinning another double cross of their hearts as she aids his escape. In conclusion the film’s cinematography and lighting together with the score transforms his sin into absolution through forgiveness. In the final frame we see the shadow of perfect sacrifice beneath the askew, prostrate body, like flawed humanity underpinned by divine grace. The BFI restore one film per year and I’m very glad they chose this one, however I’m even gladder that I saw it for the first time with such astute accompanists!

By way of introduction to The Informer the Hipp Fest tradition of accompanying features with shorts provided an opportunity for reflection on historical fictions and how archival footage can reveal our changing relationship with the past. A three minute British newsreel from 6th May 1916, filmed one week after the Easter rising in the fight for a free Irish state was accompanied very subtlety by Mike Nolan on piano. Viewing the sobering footage of British soldiers and smoking buildings conveying authority without explanation or justification was informed by the alternative voice of the piano. The accompaniment introduced emotional intelligence and powers of hindsight to the clip. The fake news on this day was the imagery of marching troops asserting colonial authority and control, deemed sufficient reportage on its own to reassure the British public. Seeing such events through an archival lens often forces us to re-examine attitudes and behaviours in the present, rather than simply assuming that now =progress. As a backdrop to the feature it was not just a historically linked news story but a timely reflective pause.

The ever popular Laurel and Hardy Triple Bill is an annual Hipp Fest tradition that always demands an encore. The universal appeal of Silent Film comedians such as Laurel & Hardy, Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin with their visual/ physical comedy setups crosses all generations, borders and potential language barriers. The entire world loves to laugh and there is nothing better or more restorative to the soul than collective laughter. Stan’s “thought free innocence” partnered with Ollie’s adult pomposity is a wondrous recipe for glee. The selection of three 19 minute shorts from 1927-28 accompanied by the superb John Sweeney on piano provided a gloriously sunny afternoon’s entertainment, equal to the unbelievably bright Spring weather outside. In Putting Pants on Philip Stan Laurel plays the visiting Scottish cousin of J. Piedmont Mumblethunder (Oliver Hardy) who tries to convince him (unsuccessfully) to wear pants instead of his kilt and stop chasing women. In The Finishing Touch Stan and Ollie are unleashed as unlikely house builders, falling foul of the law, the local sanatorium and causing unwitting destruction and hilarity. However the best was saved till last with the Scottish premiere of the complete two reel version of The Battle of the Century, recently restored by Lobster Films in France using newly discovered footage. It is always miraculous when missing film is discovered, because it can then be rediscovered by contemporary audiences with timeless enthusiasm and delight. What’s not to love about a progressively escalating finale featuring Stan, Ollie, a parked LA Pie Co van, the inhabitants of an entire town and 4000 custard pies?!

The closing night gala brought together Stephen Horne (piano, accordion, flute) and Frank Bockius (percussion) for a superlative performance of Chicago (1927). Sometimes in performance masterful musicianship, pure intuition, expert timing and unique rapport all combine to deliver something very special. Clearly they were having great fun accompanying this film and that invigorating energy was completely infectious. The bold, brassy tale of media darling and murderess Roxie Hart (magnificently played by Phyllis Haver) is a rich source of satirical comedy, even more strikingly relevant today than when the film was made. Directed by Frank Urson and Cecil.B.DeMille the story of Chicago is based on Maurine Dallas Watkins 1926 Broadway play, inspired by two separate real life murder cases Watkins covered as a journalist for the Chicago Tribune in 1924. The tone is glitzy and sensational but also very cynically grounded in an age of mass media where being famous, pretty or both is enough to get away with murder.

The upbeat musical introduction set the scene for a party loving atmosphere of bright lights, big city with brash cymbals, jaunty phrasing and instrumental rhythmic refrain of “Chicago!” “Chicago!” That free-spirited optimism is paired with the intertitle reference to “a little girl who was all wrong”. The child/ woman in question is Roxie Hart who we first meet while she’s still asleep, lovingly observed by her doting husband who is busy doing chores and making her breakfast. The voice of the solo piano leaves us in no doubt as to his genuine love for his wife. As she slyly opens her eyes the sassy movement of brushes on the snare drum and the tinny sound of her garter bells her husband picks up off the floor lead us to the conclusion, without a word of dialogue, that her relationship with him is entirely one of convenience. The sonic judgement is that she is both cunning and shamelessly hollow. As Roxie’s husband Amos leaves for work he meets their young cleaning lady Katie on the stairs and trembling percussion reveals what’s in her heart. This quietly subtle, unexpected instrumentation heightens our sense of the brief, awkward exchange between them. The man with Roxie’s other garter is her rich older lover who tired of receiving endless bills for perfume, clothes and lingerie decides he’s had enough and threatens to leave her. In this apartment scene a portable keyboard above the piano stands in for the fairground –like sound of the pianola (self-playing piano) imitating joviality. The period dance tune “Ain’t She Sweet” aligns with Roxie’s annoyingly persuasive baby talk, the profusion of kewpie dolls in the apartment and is revived with mocking irony when she’s throwing a tantrum, deviously trying to get her own way or trying to throttle a rival in a hilarious prison cat fight. That capacity to tap into a character’s motivation and musically comment on it, sometimes in sharp contrast to what the character is doing to convince themselves or others around them on screen is a masterful skill.

When her usual seductive tactics fail and it becomes apparent that her human wad of cash is about to walk out the door, Roxie’s eyes narrow as piano and drum plumb the depths of her vindictive outrage. She picks up the gun and shoots her lover, then turns on the melodrama to mask her adultery in phoning her husband to come and rescue her. When he finds Roxie’s garter in the dead man’s pocket the deception becomes clear, unfurling like the inner range of the piano which deepens with his expression. As he throws the garter to the floor, silence is the strongest accent of dramatic recognition in that moment and it is intuitively given. Stephen Horne’s accompaniment for Silent Film is characteristically insightful and ingenious. The human story on screen is distilled in his music with emotional investment and thoughtful restraint. Both silence and sound have value and if high drama enters the frame then it is never translated into a clumsy, illustrative musical cliché, but something far more humanely nuanced and relatable. Frank Bockius is an equally versatile and accomplished musician, achieving percussive textures that take the audience beneath Chicago’s jazzy surface to a far more interesting psychological and imaginative space. Together these two musicians were astonishing to watch, like two halves of one mind in total unision. Their semi improvised approach allowed considered reflection within the story and freedom of expression with all parts equal to the spirit of the film. It’s the energy, artistry, imagination and commitment I hope for every time I go to a live Silent, which admittedly sets a very high bar, not just in performance but interpretation.

The range, depth and versatility of both musicians is quite extraordinary. When we see one of Roxie’s fellow prison inmates Charleston Lou (“who knifed her sweetie”) reading a book of Standard Etiquette with the chapter heading “Correct use of a knife” a pressured drum stick drawn across a cymbal helps deliver the joke. Corrupt lawyer Billy Flynn is introduced to us by the sound of the accordion adopting his seasoned, well-heeled swagger and the flute is used, not for sweet ethereal airs but as an instrument of licentious persuasion when Roxie needs to bat her eyelashes to get what she wants. When Roxie’s husband is reduced to stealing money from Flynn to pay his wife’s legal bill, breaking a vase in his night-time raid and alerting Flynn’s butler, percussive precision takes the audience to the centre of the action. Hollow wooden beats and the hand used across the breadth of the drum surface allows us to viscerally move with them in the struggle. Flynn’s highly amusing coaching of Roxie in how to behave during her trial is wryly aided by the plotting calculation of the piano. Instructed to wear masks of bravery, innocence, virtue and “droop” when attacked by the prosecution the sound of the kazoo accompanies her act of purity in the comical farce of the courtroom. The all-male jury are way too busy eyeing Roxie’s legs to listen to the evidence and when her defence appeals to them as “men of intelligence” the piano comments to the contrary. In Flynn’s closing argument “Heavenly bells” of judgement are actually cow bells on a passing cart outside and Roxie walks out of court scot-free, continuing to milk the publicity and posing for photographs. However she soon becomes yesterday’s news when Two Gun Rosy enters the courthouse and her husband finally comes to his senses and throws her out. The Kewpie doll and porcelain clown on the mantelpiece are smashed along with Amos’s image of himself in the mirror. On the rainy street outside Roxie sees her trial headlines trodden underfoot, a sequence borrowed by Michel Hazanavicius in his 2011 Silent film The Artist. She watches as her fame and fortune is swept into the gutter and down a storm drain. But all is not lost for husband Amos when Katie comes in to tidily console him and we are assured by the rousing, instrumental refrain of “Chicago!” “Chicago!” that happiness is just around the corner. In twelve months’ time (and counting) another Hipp Fest will be too!

Hipp Fest Website:

http://www.falkirkcommunitytrust.org/venues/hippodrome/silent-cinema/

Hipp Fest 2017 Programme: