Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow 17 June – 9 September 2023

Iconic award-winning artist Pinkie Maclure has been blazing a trail in visual art and music for over thirty years. Co-writing ten albums with musician and sound designer John Wills and revolutionising the art of stained glass, Maclure’s art is a potent, beautifully realised form of activism. Her ability to bring the most pressing issues and anxieties of our age into the light with power and compassion, resists dogma and triggers consciousness through imagination.

Maclure’s recent exhibitions at Homo Faber (Venice), Collect (London), the Outsider Art Fair (New York), the John Ruskin Prize (Manchester) and awards including the Sequested Prize, John Byrne Prize, Zealous Craft Prize and Jerwood Makers, have contributed to the artist’s growing international following. Represented in the National Museum of Scotland collection and private collections worldwide, Maclure’s distinctive voice as a visual artist, vocalist and musician has resounding impact. Her debut solo exhibition Lost Congregation at CCA Glasgow, is a thoroughly immersive and haunting experience. The show consists of three rooms of stained-glass, a 3D ambisonics sound installation and moving image, together with a series of live performances by the artist. In addition to new work, the exhibition is also a survey of key works from 2017-2023, including Pills for Ills, Ills for Pills (2018), addressing Britain’s opioid epidemic and Beauty Tricks (2017) a multilayered expose of the environmental and psychological cost of the beauty industry. (Discussed in a previous essay Pinkie Maclure– Beauty Tricks https://www.kilmorackgallery.co.uk/pinkie-maclure-beaty-tricks-essay/ )

Tackling the enormous sense of grief and loss felt by many people seeing ecological collapse unfold in real time, Maclure offers a vision of hope and connectivity with Nature’s capacity for renewal. It’s this spirit that enables you to emerge from the exhibition having faced the reality of climate crisis, human displacement, and misogyny with a sense of empowerment and optimism. The central work in the show is Maclure’s installation The Soil (2023) with sound installation Dust Won’t Lie, written and sung by Pinkie Maclure with John Wills. This dark, immersive space envelops the viewer in soundscape and imagery, on the wall, projected onto the floor and in a stunning, large scale stained glass at the far end of the room. This abandoned chapel feels haunted and ethereal, but inviting, two staggered groups of cushioned pews and Maclure’s mesmerising voice, as if drawn from the earth in tonal descent, ground the participant. Tangles of dead branches and the crunch of leaves underfoot evoke a kind of passing. An expression of human experience and resilience, Somehow We Mend (2023), reveals itself in the gloom, the eye directed to the wall work by an extended branch. A red thread connects the hand of a figure to a sewn and drawn panel with words, some censored or obliterated by ink, burnt cigarette holes and a band aid.

I UNSTUCK MYSELF FROM

SOMEONE’S SHOE

PEELED BACK THE SOUL AND

WALKED OUT

ALL THE WAY TO

THE BROW OF THE HILL WHERE

THE SILK

HUNG FROM THE TREES

SOMEHOW WE MEND, SOMEHOW,

SOMEHOW WE MEND IN THE END’

Photograph by Alan Dimmick, courtesy of the artist.

This element of the installation is poignant and deeply affecting in its acknowledgement of lived experience, bringing the personal into what is historically held as a communal and religious space. Perception shifts in the shimmering projected light on the floor, where faces emerge and recede, like reflections in a pool of water, artist, youth, and crone goddess, digging deep beneath man-made architecture. Other elements of the soundscape provoke and soothe in contemplation, some are drawn from tradition, land and collective memory, the voices of women waulking cloth, a masculine voice in Scots song, calling children in from play, whispers, zooming traffic and the overarching statement of lament; ‘The Dust won’t lie.’ Is this because it is being stirred and disturbed, or because the earth and the dust we become speaks the ultimate truth? I find myself writing first about sound, because of the immediacy of being drawn sonically into the space, then there is light. Maclure’s large 3m x 2m stained glass is a revelation borne of all the thoughts, emotions and questions which swirl 360 degrees around the participant in the dark. In a reactionary age of fear and survival, Maclure brings much needed critical mass and ancient wisdom to the fore.

Photograph by Alan Dimmick, courtesy of the artist.

Her gothic peaked triptych of stained glass is a magnificent centrepiece, largely comprised of salvaged glass from a ‘Victorian greenhouse that blew down in a storm.’ The use of material feels poetic and ironic, a composition borne of destructive weather patterns of the Anthropocene. The central figure is radiant with questioning, her head tilted, gazing upwards, a flaxen haired Joan of Arc-like protagonist, hands clasped in prayer. Gardening gloves, wellies and fishnet tights bring her down to earth and the stream of urine which becomes a flowing stratum beneath her feet anchors the human body to nature’s eternal cycles. It is Maclure’s response to the horrifying prediction reported by the UN that ‘the world could run out of topsoil in sixty years’, also drawing on the knowledge that human urine contains nitrogen, potassium and phosphorous, ‘nutrients essential to healthy plant growth.’ That saintly vision, deferring authority to a divine God is delivered squarely into our hands. We are part of the body of nature and can be agents of regeneration, rather than destruction, if we choose. At the base of the composition, plants, microbes, fossil and seed forms give a sense of propensity to growth, a cycle of life starting again in a discarded banana and mouldy pie sprouting seedlings. The fragility of glass and the fractured word ‘Frag’ ‘ile’ in the upper black and white world of the composition, meets the ‘Fragile’ complete, written red in depths of soil. The upper section dominated by humanity is filled with fractured lines and industrial wires, fallow plough lines and delicate marks like those of ink suspension in water. It feels like a dystopian future, which of course is now. The narrative unfolds in each considered element. Magic, rage, loss, critical interrogation, compassion, humility, hope, and empowerment circulate throughout the exhibition.

Future Daysies (2023) asks what will we choose to nurture as a species, a hand raised, pointing upwards, an illuminated nucleus of cell division in the upper right and a mass of potential life below, or is it just a bloody soup of destruction? The hand and the light lift the spirit in favour of resilience, with or without God, a refrain of ‘somehow we mend.’

Photograph courtesy of the artist.

The idea of Future Daysies could also apply to Maclure’s Two Witches (Knowledge is Power) 2021, an unexpected vision of adolescence on the cusp of womanhood, coming into power and divining true agency. I say unexpected, because images of feminine youth, possessed of knowledge and potentiality are so rare. The words ‘knowledge is power’ written ‘in seven of the world’s most used languages’ wraps itself around the globe. Patriarchal societies excluding women are deposed by Maclure’s ‘winking owl’, ‘defecating on a freemasonry emblem’. Knowledge of the natural world is exalted in the torch attracting moths and self-determination in relation to one’s own body is celebrated in the flagpole flying a condom. It’s a powerful declaration of potential, and beauty in potential, that shines brightly in the darkest of spaces. Popular culture and oppressive regimes do not allow such expression of feminine strength and Maclure smashes the ceiling with her mighty, fragile art- it’s a wonderful thing to witness. Seeing visitors to the exhibition studying the intricate details, debate meanings and make connections with their own experiences was also a joy. This is what art is meant to do.

Completed ‘at the heights of the pandemic’ Maclure’s Totally Wired (Self Portrait with Insomnia Posy) 2020 reads as an awakening, not just from physical sleep or through a nightmare, but in the linear fracture of stained glass that rests on the artist’s forehead like a third eye. Intense blue and frenzied black drawn marks halo the portrait, with ‘the waving hands of friends on Zoom’ scattered above, ‘imprinted’ in the artist’s mind like a constellation of stars. It’s a response to horror and tragedy that reconstructs humanity, in the care and crafting of stained-glass. The split line pupils give a sense of altered perception and profound unease, contrasted with the warm toned, floral, lace textured blanket which the artist clutches to her chest. Held there too, is the comfort of Nature, a posy of herbs which in that moment is subdued by a man-made global crisis. The contradictory nature of Maclure’s art is true to life, in the profound need for confrontation and comfort. When I say comfort, I’m not talking about cosy distraction or denial, but the enduring, transformative action of hope, which lives first in the imagination.

Photograph courtesy of the artist

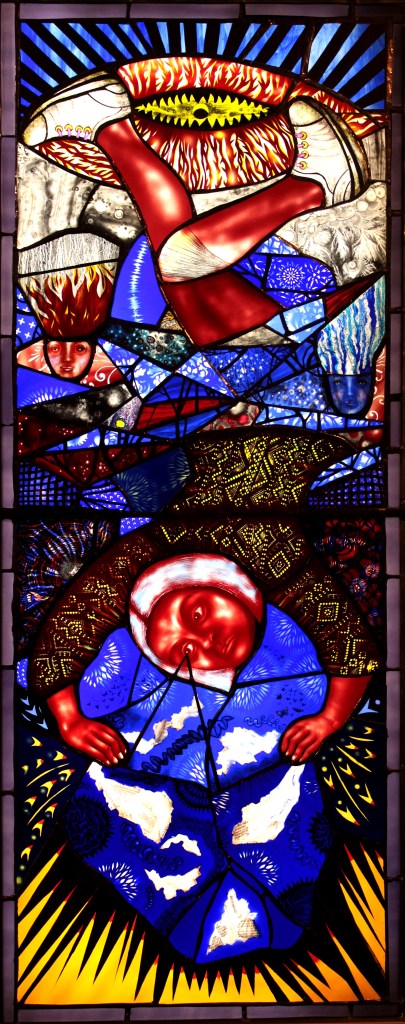

Although X-Ray Eye (2023) addresses a post truth world, the ‘twisting of words and fragmentation of social interaction’, it also recalls a strong cultural tradition of truth, in folk music and in the work of artists such as William Blake. Stephen Ellcock and Matt Osman’s book England on Fire, which features Maclure’s Green Man Searches for Wilderness (2020) taps into a seam of ancient knowing and divinity of imagination. In X-Ray Eye, Maclure’s female figure plunges head first, downward, like Blake’s The Simoniac Pope in the inferno. Though injured, she is far from helpless, flanked by opposing forces, fire and water, divided by argument, her hands pull words and assumptions apart, the fractured lead lines converging on her eye. The dominant colour within this space of exploration is the divine, sacred blue of medieval glass. Her sneakered feet straddle a portal of instinctual knowing at the apex of the composition. The body is fragmented, in a fallen position of discomfort, but there is also a will to understand that we feel will bring clarity, even in a climate of screaming opposition.

Walking away from the exhibition down Sauchiehall Street I saw a black and white poster with a lighthouse on it ‘The seas are rising and so are we’, a slogan adopted by climate activists. I had to smile, as the red, life affirming thread throughout Maclure’s extraordinary exhibition altered my perception of the world outside. ‘Somehow we mend, Somehow we mend in the end.’

Pinkie Maclure’s Lost Congregation continues at the Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow until 9 September 2023. https://www.cca-glasgow.com/programme/lost-congregation