Dovecot Studios, Edinburgh, 28 July 2023 – January 2024

Picture Phil Wilkinson / Dovecot Studios

Walking across the North Bridge in Edinburgh on my way to see the Scottish Women Artists exhibition, I saw this poster by https://artistsforwomanlifefreedom.com/ and Jack Arts.

Picture: Georgina Coburn.

The central question posed by artist Abbas Zahedi stopped me in my tracks. This text, and the slogan above, ‘Woman, Life. Freedom’, used by the Kurdish Women’s movement and more recently in solidarity with Iranian women and girls fighting for equality, was a stark reminder of women’s rights/human rights in retrograde globally. The internal diagram in the left-hand panel by Koushna Navabi had a sticker applied to the womb, branded like a graffiti tag, perhaps reclaiming that space of origin. More disturbingly, the right-hand panel by Hadi Falapishi appeared to have been defaced, a section torn away to obscure the standing female figure with her arms outstretched. Cultures of oppression are everywhere- some more subtle than others.

Glancing to my right, I could see the banner over the City Art Centre for yet another capital male blockbuster – Peter Howson, whose testosterone fuelled paintings simply mirror the source of war and misogyny. Arguably a retrospective by Joyce W Cairns, including her large-scale cycle of War Tourist works, could have easily occupied the same space, bringing mastery of the medium and understanding of the human condition powerfully into play. Elected the first female president of the Royal Scottish Academy in 2018, Cairns’ astonishing body of work is represented by a single painting of intimate scale (Eastern Approaches c1999) in the Scottish Women Artists exhibition, a missed opportunity for the Edinburgh art world and the world visiting Edinburgh, to see the depth and breadth it has been missing from artists based outwith the central belt.

Although there are some incredible gems in this show, including works by Phoebe Anna Traquair, Bessie MacNicol, Frances MacDonald MacNair, Hannah Frank, Beatrice Huntington, Wilhelmina Barnes Graham, Margot Sandeman, Joan Eardley, Agnes Parker Miller, Frances Walker, Alberta Whittle, Helen Flockhart and Sam Ainsley, there are also many absences in the implied national survey of Scottish Women Artists. The exhibition mainly centres on works owned by the Fleming Collection and no doubt reflects historical patterns of collection and curation, as it does contemporary cultural accounting. The very term ‘Women Artists’, or ‘Women’s Art,’ has a host of associations pinned against it and I found myself wondering about how such ideas informed what I was seeing in terms of subject matter, institutional curation, and thematic bent.

While I can have no argument with the celebratory intention of the show, who remains unknown, or unshown, and why is a topic ripe for discussion, socially, culturally, and geographically. There is also a somewhat naïve premise in the narrative of this show, an assumption of superiority over the past; ‘In an era when women lead Scotland’s galleries and art schools, it is easy to forget the prejudices and barriers their predecessors have faced.’ Really? I think the question persists about how many women today are denied the ‘opportunity to seek or develop an artistic career’, or in a wider context, if they are able to pursue any career, the value attributed and actually paid for their work. The ‘marriage bar’ to female employment may no longer exist, but the question of equality and entitlement persists, heightened by the British Class system, the current cost of living crisis and the socio-economic conditions the vast majority of women consistently find themselves in. Yes, there have been strides forward in representation, but cultural attribution of value for women, together with equality, has a very long way to go.

Walking into the show the viewer is confronted with a polarity of art historical quotes; Artemesia Gentileschi’s battle cry ‘I’ll show you what a woman can do’ (1649) and art critic John Ruskin’s ridiculous claim that ‘There never having been such a being yet as a lady who could paint’ (1858). Perhaps more useful than a ‘Yes we can!’, ‘No you can’t!’ posturing is another quote on the wall at the start of the exhibition by Dame Ethel Walker in 1958.

‘There is no such thing as a woman artist. There are only two kinds of artist- bad and good.’

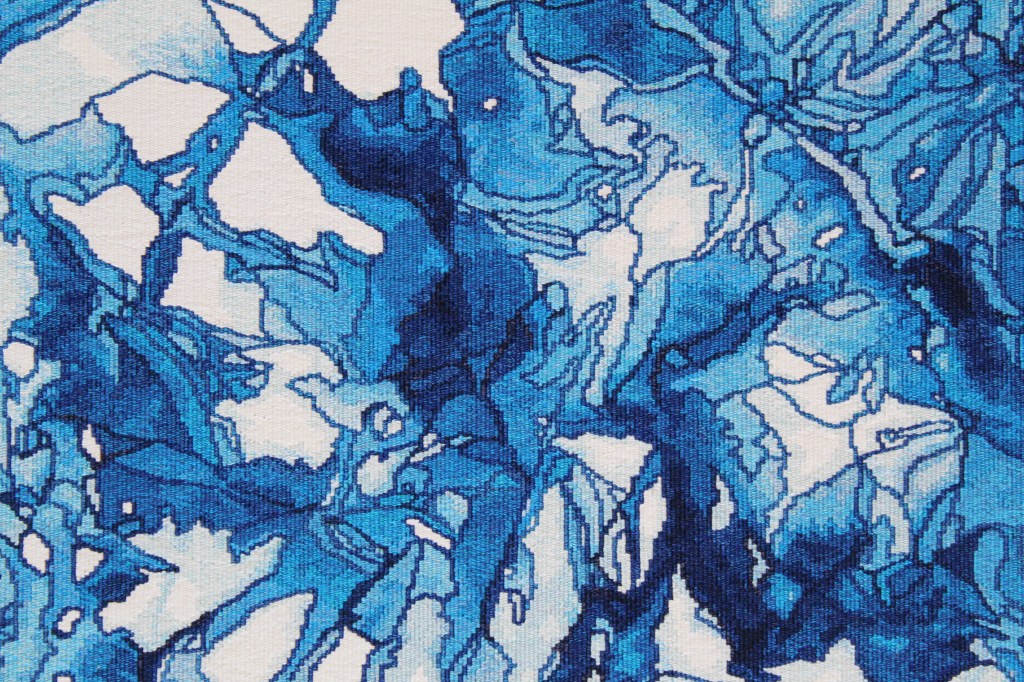

In the spirit of Dame Ethel Walker, I have to say that I found some of the examples of work by Scottish Women Artists disappointing, particularly in the contemporary / final section of the show, which felt tokenistic, given the emphasis on 20th Century and earlier works. I left the gallery feeling unconvinced and wanting when I should have been punching the air. The title ‘Scottish Women Artists – 250 Years of Challenging Perception’ didn’t necessarily match what I saw on display – perhaps because it wasn’t challenging perception enough overall. Works like Alberta Whittle’s Entanglement is More Than Blood (2021-22, watercolour on paper) which articulates the complexity of identity so beautifully in its ever-questioning serpentine forms, contrasted sharply with works such as Rachel Maclean’s garish, simplistic treatment of body dysmorphia I’m Fine/Save Mi, 2021. Rug, gun tufted. Wool, polypropylene and canvas) or Sekai Machache’s Lively Blue tapestry (2023), which gains meaning through accompanying text. Based on an expressive abstract ink drawing and Machache’s investigation of the Colonial History of indigo, it is arguably not the best example of her work in comparison to the artist’s more challenging, nuanced film and photographic works.

Picture Phil Wilkinson / Dovecot Studios

Sam Ainsley’s This Land is Your Land (2012, digital pigment print, on loan from Glasgow Women’s Library) with its coastline of word association and multilayered provocation, felt like a Rorschach blot test, facing and meeting forms of self-identification. It’s a work that like the best in the show, provides a trigger for questions, stories, and further explorations. Standing in front of Bessie MacNicol’s Portrait of Hornel (1896, oil on canvas, National Trust for Scotland, Broughton House and Garden) it is impossible not to feel the loss of an artistic trajectory cut short by death in childbirth. MacNicol’s paint handling and masterful, emotionally intelligent rendering of her sitter, triggers the imagination. In the context of this exhibition, what is most impressive is her resounding presence as she meets the eye of a fellow male artist as an equal, in every single mark. Her intention, all her knowing and understanding of medium and subject, her visual language distilled, still speaks 119 years after her death.

Many questions remain- what does it mean to be a Scottish artist or a Woman artist and who owns culture? Perhaps one of the most pertinent questions of all, triggered by a billboard on the way to the exhibition.

https://dovecotstudios.com/exhibitions/scottish-women-artists