What first drew you to this artist’s work?

A tip off! Back in 2006, I was about to start work on a research project on Visual Arts in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. A gallery owner told me that if I was going to the Western Isles, then I should speak to the sculptor Steve Dilworth. This first led me to the artist’s work, which had immediate impact- it was so powerful and intriguing.

Intriguing how?

It felt both alive and ancient. There was something about the forms which resonated, particularly the throwing objects, which were some of the first objects I saw. Also, there was a sense of mystery. With many of Dilworth’s objects you can’t see what is inside them, so there is an element of belief in play, which is interesting. His work looked like it had been dug up out of the earth, like an ancient archaeological find. I felt it was tapping into something very deep in the human psyche, something needed.

Needed?

Yes, almost answering an unconscious call- but perhaps with a question rather than an answer! I’ve always been drawn to art that creates a space for your imagination to wander into and challenges perception on some level. I think it’s good to have to work a bit to discover what makes it tick.

Like a puzzle to be solved?

Yes, but it’s more than just a game. It relates to intention and value.

What is Dilworth’s intention and value as an artist?

‘What makes a Dilworth’ is a question I set out to answer with the book. Whether I’ve succeeded or not is for the reader to decide, but I think the artist’s intention, as he has said himself, is to ask questions rather than to give answers. There is a will to try and understand what we are as humans and why we’re here, something that our secular age and consumer culture completely fails to address. The crafting of Dilworth’s objects and the energy of material as a point of ignition is really important in his work, it’s what drives it. I think Dilworth’s art, like all great art, triggers essential connections, to our ancestors, each other and the earth we stand upon. It can be comforting in some ways and very confronting as well-that is its value.

Confronting in what way?

In Dilworth’s work as in Nature, death and decay are part of life, part of a natural cycle. So his work can be very confronting in terms of what we fear most and deny on a daily basis, particularly in Western culture. In many of Dilworth’s works you can see the preserved body of a bird or animal, in the case of the Hanging Figure, a human skeleton, which is part of the whole, crafted with care and reverence. It isn’t hidden but made visible again, rendered sacred. His work acknowledges that we are part of Nature, part of something bigger than ourselves. I think his work calls upon us to remember that collective understanding and to actively use our imaginations. His work isn’t passive in that respect, it makes demands on the participant.

In your introduction to the book, you talk about the the ‘energetic charge at the heart’ of Dilworth’s work, crafted from the inside out, which triggers genetic memory’, and ‘the human drive to out create destruction’, are the two linked?

That’s a big question! But yes, I think the human drive to out create destruction through imagination is humanity’s greatest asset and the key if we are to survive as a species. It is also an individual artist’s key, not just to survival, but evolution and distillation of their practice. Being driven to make things over the course of a lifetime is a difficult path, but it is essentially a hopeful act. The artist is taking raw materials or energies and transforming them, altering perception in the process, for them and the viewer. The crafting of natural materials in particular calls upon centuries of understanding, of history and lore, knowledge of the natural environment, conscious and unconscious, in the making. This tactile communication is something we have lost in a post pandemic, digital age, and need to remember again. So yes, I think the human drive to out create destruction is an essential part of our hardwiring as humans, and remembering that isn’t just relevant to Dilworth’s art, but to surviving the critical age we’re living in. Creativity is an essential part of being human and we forget that at our peril.

How did you start to investigate the artist’s work?

After I first interviewed Dilworth in 2006, I wrote several articles about the artist, attended exhibitions, saw the work progressing, and by 2014 decided that as there was still so little information about him in the public domain, it was time to write something more substantial. Awareness of artists based in Scotland in rest of the UK is generally poor, equally within Scotland, artists based in the Highlands and Islands, outside the central belt, have even less coverage, so entering public consciousness is a long process. In thinking about a Dilworth biography my first port of call was the artist- without his cooperation, a book like this one would be impossible to write. Initially we discussed key works in his trajectory. I knew that the book needed to be driven by the work and its evolution, and it grew from there, from ongoing dialogue with the artist.

What were some of the challenges in researching a book about a living artist?

(Laughing)The weight of responsibility and the sheer volume of primary information! Not just in relation to the individual artist and doing justice to what I felt was important work, but in relation to all the interviewees. A bit like documentary film making on a living subject, there are a lot of sensitivities. To write about someone’s life in the now, you have to establish trust, and you come to know and gather far more information than you can ever fit into a single book. There is a huge amount of research and admin before you actually begin writing, and you also have to be prepared to go where the research takes you, beyond your original question or motivation. In 2014 the starting point was constructing a master list of Dilworth’s work and tracking it down, which took about three years. Then there were hundreds of hours of interviews, transcribing, checking facts, corroborating stories wherever possible, and checking back with interviewees over several years. It was very time intensive, and I didn’t have any backing for the book until very late in 2022. Keeping a project going for years, with no certainty of publication was difficult. A living artist’s work is still being created, so keeping up to date with it, as the book and the artist evolved, was something I needed to be conscious of too. It’s a changing landscape rather than a finite set of historical works and circumstances to grapple with. Writing about a living artist you have to be respectful but sometimes sceptical too, human memory is fallible, and people’s experiences of the same event can be quite different. There is a balance to be struck between the question you are trying to answer, the artist’s work and the person standing in front of you. Hero worship doesn’t help and inevitably crumbles, so the work has to carry the conviction, that it is important enough to be written about- and that I never doubted for a second. The research brought me into contact with interviewees who shared that conviction too, and that was fortifying as work on the book progressed over many years.

What is unique about the book and how did it take shape?

I think the way that it weaves together different stories, experiences, and disciplines makes it different. It is part biography, part memoir-in being based on the recollections of a living artist, it’s an in-depth examination of the artist’s work and draws on interviews with custodians of Dilworth’s objects, how they live with these works and interact with them. I think that perspective, of what happens when a work leaves the artist’s studio and enters everyday life, is rarely documented. Significantly Dilworth’s work isn’t just looked at but is integrated into people’s lives on a very deep level and that makes it unique. Through the artist’s work, the book examines our relationship with nature and material, and hopefully, like the artist’s work, raises questions. Following the research phase, which was like tracing the family, genus and species of living things, when I was first thinking about the shape of the book, I drew it on an enormous sheet of paper, mapping key works and themes and twelve sections grew naturally out of that. I think the biggest challenge was integrating a vast amount of information and testimony, and most importantly not explaining the work away. It’s the challenge of writing about something timeless and infinite using finite language- a bit of a tightrope walk! When you are researching from scratch, every fact and story is hard won, but you can’t include everything, so I had to be pretty ruthless with the editing. The first draft was about 10,000 words longer than the final version.

How did your experience shape your approach to the book?

I sit rather oddly between multiple disciplines, and I grew up in Australia, where the British class system and its cultural hierarchies are less ingrained, so my approach to all forms of art practice from Craft to Conceptual and between disciplines is very fluid. My academic background is Art History, but I’m an independent researcher, I’m not attached to a university or any other cultural institution in the UK. I’m a freelance arts writer so I’m used to unpacking work in reviews, interviews and features, but I’m also a blogger on my own site, which gives freedom to write about what interests you most, and in more detail, outside someone else’s brief or house style. I’m used to spending a lot of time talking directly to artists in their studios, something I have always enjoyed doing, and following the development of their work over a long period of time, so this kind of book is a natural fit. I’ve worked for galleries too, so I have an understanding of the commercial and promotional side of things, but probably what affects my approach more than anything else is having an understanding of making and what that process actually involves. I think the way I analyse work is driven by coming to grips with the creative process and intention behind it. Alongside hands on making in different media, I’m grateful for my Art History background, it’s the part of my brain that can take a bird’s eye view and look for the wider, international context of someone’s practice. In non-fiction writing, the academic angle is often frowned upon, narrative non- fiction is the buzz right now, but I think there is room for many different perspectives, or a blend of them. I think people can cope with footnotes provided the story is an interesting one.

Are there other influences in your art writing?

As a child I was introduced to the history of photography and cinema through my father and when I was studying as an undergrad, my foundation year was cross disciplinary – visual art, German studies and the history of Western music, so there was a lot of cross-fertilisation. In terms of art writing, it wasn’t the theory side that appealed to me- often that was just full of self-aggrandizing jargon, that had more to do with the writer’s ego and little to do with the artist’s actual work. I’m not anti-theory, but the authenticity of straight from the horse’s mouth definitely has more appeal! Reading David Sylvester’s interviews with Francis Bacon, Tarkovsky’s Sculpting in Time: Reflections on the Cinema, or Van Gogh’s letters to his brother Theo, reveals very directly what fired their work and why it matters in human terms. I’ve spent a lot of time over the last twenty plus years in artist’s studios asking questions and coming to terms with what makes their work tick. When I write about any artist, I would hope that what I write would lead people back to their original work in a meaningful way. The strength of art is the connections made in our own imaginations, linked to the wider world. It’s why I ask the question in chapter one about ‘How do we know who we are?’ Writing about artists that are overlooked is also an important part of my writing.

Why do you think Steve Dilworth’s work has been overlooked historically?

He’s never chased fame and was emerging at a time when the value of a piece of work, rather than its making or intention was the headline. Damian Hirst’s diamond encrusted skull For the Love of God and a Dilworth Calm Water object are about as far apart in intention as it is possible to be. Although Dilworth has a dedicated following which has steadily grown in recent years, most of his work is in private hands rather than public facing collections, so opportunities to see his work and enter public consciousness have been limited. His work can be challenging and confrontational in terms of materials and it’s difficult to classify – it is of itself and doesn’t particularly relate to other artists or movements. It’s brand resistant, and he lives in a place that few arts correspondents or journalists are ever sent to. Also, contrary to the demands of making anything in a capitalist society, many of his works have not been made with a commercial end space in mind, such as handheld commemorative objects or his landworks.

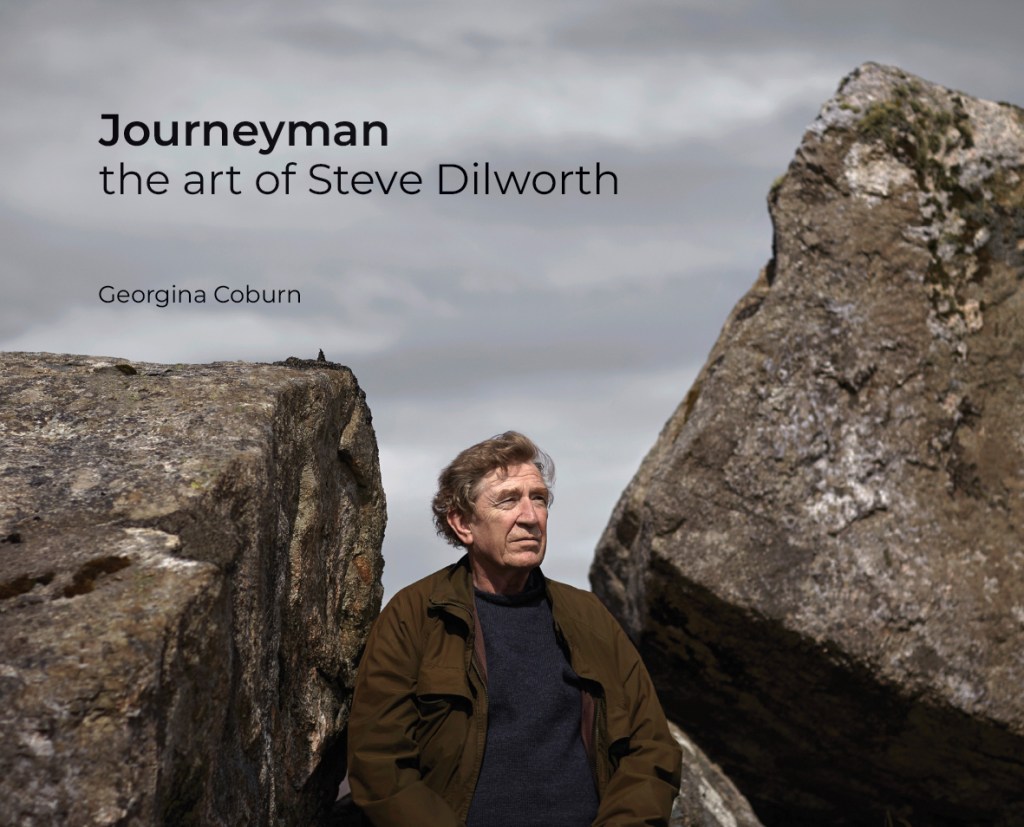

Why did you call the book Journeyman?

I chose that title because on many levels, all of Dilworth’s work and trajectory takes the participant on a journey of discovery. I also use it in the sense that for the artist and the audience, there isn’t a fixed meaning or destination. The work is timeless and often reveals itself over many years, like a lifelong companion. There is some irony in there too- a journeyman is a word used to describe a skilled worker between an apprentice and a master. Steve describes himself ‘like an idiot being given the keys to the library’, regardless of advancing skill or accomplishment, which is self-deprecating, a sentiment many artists’ share. I also believe that Art is a life choice where nobody gets to arrive- if you think you have, that you’ve mastered it all, then you’ve lost the game entirely. So, it is a play on those ideas too. I don’t believe in the Romantic idea of genius. Creative work, the kind that lasts, is hard graft, and requires lifelong dedication.

What are your hopes for the book, now that it has finally been published?

I hope that the artist and all the contributors feel their stories have been well told, and that the book leads people back to Dilworth’s original work in a meaningful way. There are many artists based in the North whose stories have yet to be told, so I hope that this book paves the way for a wider conversation about where the real centres of cultural gravity are, and why they matter, perhaps now more than ever.

29 December 2023.